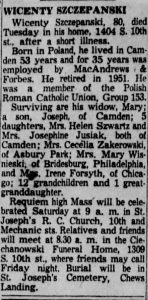

My great grandfather Wicenty (Vincent) Szczepanski is a little bit of a mystery to me. He was born on 20 June 1874 in what we think was Warsaw, Poland. According to census reports, he probably immigrated to the United States between 1896 and 1902. I have looked far and wide for any documents relating to his immigration here, but they remain elusive. Apparently, he hated having his picture taken, and the only image I have is blurry and overexposed as he stands next to my great grandmother Mary Nowakowska, whom he married in 1902. Although I have found little about his life before he arrived in Camden, New Jersey, Wicenty turns up in every single census record (both US and New Jersey) between 1905 and 1940. He passed away in 1955, and his obituary states that he had been a resident of Camden for 53 years of his life at the time of his death.

(Camden, New Jersey)

11 May 1955, Wed, Page 4.

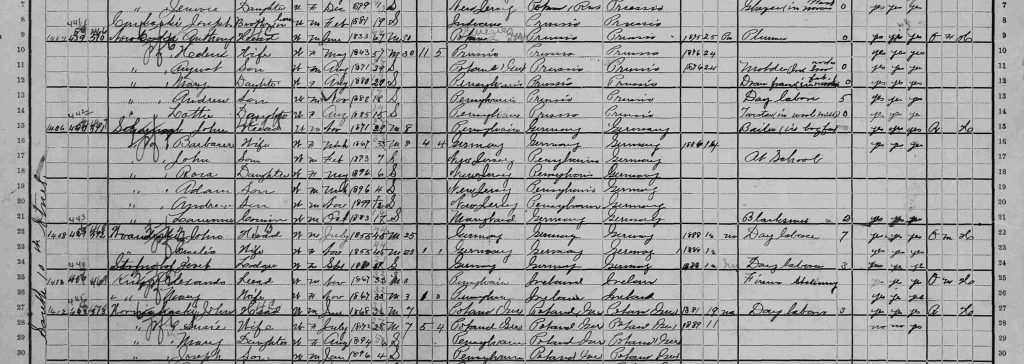

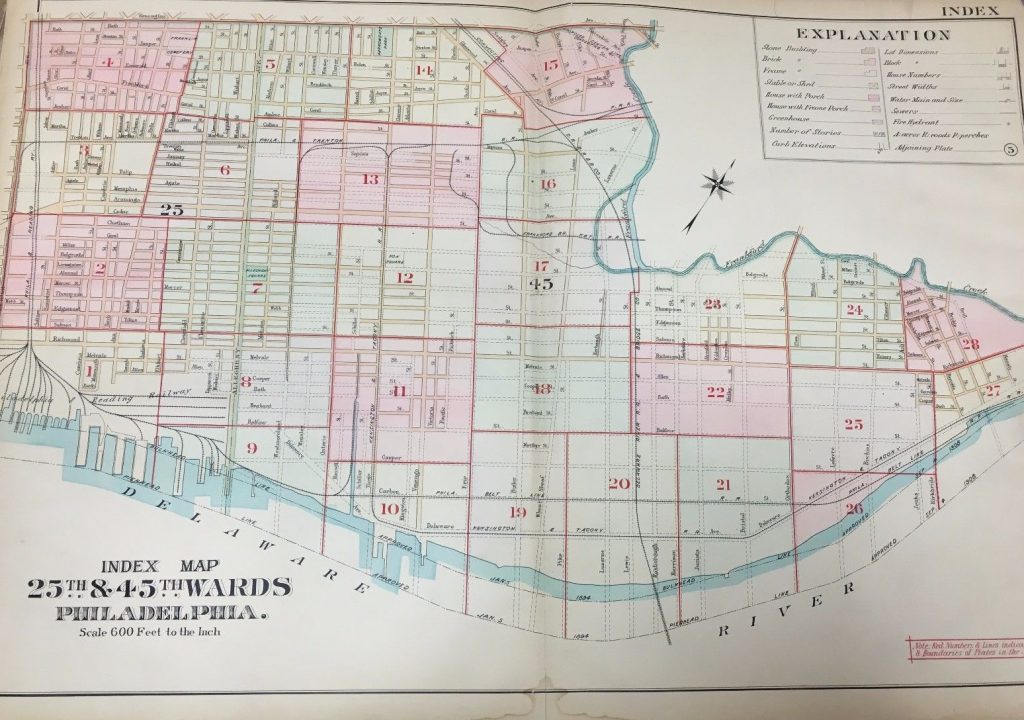

Looking at Wicenty’s life through census reports reveals how much of his experience was typical of Polish immigrants in Camden. The Szczepanski’s lived on 10th Street, across the street from St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church — a religious and cultural hub for the Polish immigrant community at S. 10th Street and Mechanic Street.Wicenty was a day laborer in the factory, and he worked in a variety of roles throughout his life including as a machinist (1905), a chipper at Locomotive W/E (1910), a leather peeler in the Peerless Kid Co. factory (1920), a laborer in a paper mill (1930), and as a factory worker as MacAndrews & Forbes, which was known for the production of licorice products. He worked in the licorice factory for a total of 35 years. It was located down on 3rd Street, and he likely walked to and from the waterfront. Although my grandfather worked in the papermill portion of the factory, I wonder if the smell of licorice lingered on his clothing after a full day of work.

Writing for the Diamond Jubilee Anniversary Book (1967), church historian Paul P. Zachary wrote about the daily lives of the founding parishioners of St. Joseph’s Church. I imagine much of this pertained to my great grandfather’s experiences. I’m quoting at length from the St. Joseph’s Church website here:

Family heads worked at the prevailing rate of ten cents an hour, from ten to fourteen hours a day with Saturday afternoons off. An average worker earned six dollars weekly. Those who brought home ten or more dollars were considered aristocrats of labor. To augment family incomes, boarders were taken in, mainly relatives or close family friends streaming in from Europe…

Before the dawn of the electrical machine age, factory equipment was operated either by hand or by steam power, and shift work in industry was virtually unknown. Where gas was unavailable, lighting came from kerosene oil lamps. Transportation to and from work was made by nickel fare trolleys, ferries or by a sturdy pair of legs. With the advent of the automobile, ten-cent jitney (bus) service competed with trolleys for the riding public…

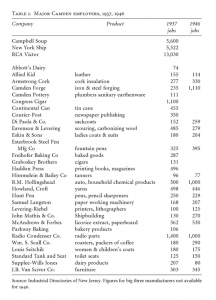

As industrial workers, men found employment in a number of diversified fields, such as Campbell Soup Company, Victor Talking Machine Company (later RCA) [now GE], Esterbrook Pen Company, International Nickel Works, Farr & Bailey (linoleum products), MacAndrew & Forbes (licorice), Armstrong Cork Company, Eavenson-Leverings and Howland Croft woolen mills. Those who traveled to Philadelphia found work at the huge Baldwin Locomotive Works (located on Broad Street), sugar plants of Quaker, MacCahan’s and Pennsylvania, or at many of the small iron and brass foundries in the area.

The Camden-Philadelphia area at the time was the world’s center for leather tanning. Some of the major tanneries employing workers of the parish in their “morocco shops” or “garbarnias,” as the Poles called them, were Keystone Leather, Allied Kid, Castle Kid, McNeely’s, John R. Evans and Surpass Leather. New York Shipbuilding Corporation, formed in 1898, was where most of the younger men were hired, including some fourteen year olds who falsified their ages. It was a common practice in those days to see bright children, whose parents needed financial aid drop out of school between the ages of twelve and fourteen.

The long hours worked by fathers kept many of them from enjoying normal family relations with their children until the weekends. They left for work while the children were still asleep. When they returned home from work, the youngsters were back in bed between the hours of seven and nine regularly every evening.

I feel like Wicenty crossed most of those bridges when he was alive and his experiences seem fairly representative for Polish immigrants at the time. Based on the value of his home at the time, I highly doubt he would have been considered one of the “aristocrats of labor” that Zachary discusses in his essay.

Wicenty’s life intersects with the commercial history of Camden as a site of industrial production. After all, MacAndrews & Forbes was one of Camden’s major employers (click to expand the table on the left). It was a company that was started by two Scottish entrepreneurs, Edward MacAndrew and William Forbes. They established a network of factories after arriving in Turkey in 1850 and finding a fortune in Glycyrrhiza Glabra (the licorice plant). Licorice is often used as a flavoring agent in American tobacco products. With the expansion of their business to the United States, they opened factories in both Newark and Camden, New Jersey. Below you can see how the factory would have looked in 1930, when my great grandfather was working there. A full history of the company was recently written by Willis Kidd for the Levantine Heritage Foundation (2016).

Listing “MacAndrew and Forbes” as a place of work on a census or a draft registration is misleading when you consider the diversity of activities that were conducted there. For example, a 1906 map of the establishment shows that much of the floor space of the factory was dedicated to the storage of licorice root in bales. But looking around the map we can also see other storage facilities, a machine shop, a grinding room, an extracting house, a laboratory, and an office. They also experimented with dyestuffs, wall-board, and foamite fire extinguishers. I know that my great grandfather identified his work place as a “paper mill,” and sure enough, MacAndrews and Forbes also shows up in trade directories of the time not as a licorice manufacturer, but as a pulp and paper mill.

Sometimes genealogy research is not about birth, marriage, and death certificates (although I take them when I can find them!) To once again cite Mr. Paul P. Zachary,

How the families lived, how they fared, and how their prayers were answered are just as important as factors of historical reference as the founding and dedication dates are, because they reflect the spirit of the day and the exact degree of progress made by both the church and the community to which they belonged…

I believe that fully exploring what life would have been like for my great grandfather Wicenty Szczepanski tells us something about the Zeitgeist of these Polish American communities at the turn of the twentieth century. In essence, it helps us paint a clearer picture of daily life in the community. I may struggle with his immigration records, but I can still imagine the larger milieu.

References

- Paul P. Zachary. “The Founding Years,” St. Joseph’s Church (n.d.; quoted from The Diamond Jubilee Anniversary Book, 1967)

- Howard Gillette Jr., Camden After the Fall: Decline and Renewal in a Post-Industrial City (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005)

- Wallis Kidd, “MacAndrews and Forbes and the Forbes Family,” Levantine Heritage Foundation (2016)

- “Camden County,” Digital Map and Geographic Data Portal. Princeton University (n.d.)

- Lockwood’s Directory of the Paper, Stationary, and Allied Trades (Lockwood Trade Journal Company, Inc., 1919)

Thank you for this insight. I’ve been doing a bit of armchair genealogy and found that my grandfather followed a similar path, arriving in Philadelphia in 1914 and landing in Camden before 1920, first at NY Ship and then spending over twenty years at the licorice works. I’m curious as to the NJ census mention. Where can they be accessed?

If you haven’t found this, I thought it helpful –

https://mapmaker.rutgers.edu/CAMDEN_COUNTY/City_of_Camden_1922.jpg

Yikes, I’m so sorry that I never saw this message! I’m so glad to hear that someone read what I put together here. I think the Licorice Works was a natural hub for many immigrants in NJ! In terms of the NJ Census, I accessed them on FamilySearch.com. While there are US Census for 1900, 1910, and 1920, the NJ Census was taken in 1905 and 1915, so it helps us get a clearer picture of the changes in between those decades. Sorry for the delayed response, but I hope your work has been progressing well!